In Africa, disinformation thrives on a terrain marked by a low literacy rate, less than 50% for countries like Chad, Mali or the Central African Republic according to UNESCO, as well as a strong oral tradition and the omnipresence of social networks such as WhatsApp, Facebook or TikTok.

Rumors often travel faster than denials, even in the most remote areas. And while French and English are used in the media, it is mainly in local languages that the majority communicate and that much of the fight against fake news is now being fought.

Social networks, catalysts for local languages

"The text is almost absent, which gives an important place to national languages, especially in countries where the literacy rate remains low."

Africa is one of the most linguistically diverse continents. With hundreds of languages spoken, this diversity is increasingly reflected on social media.

Platforms like TikTok, which focus on audio and video, reinforce this trend. "Text is almost entirely absent, which gives national languages a significant role, especially in countries where literacy rates remain low," emphasizes Georges Attino, journalist and fact-checker.

Local languages thus become a lever for accessibility: they bring information closer to populations who do not speak French or English, languages that are still too dominant in the African media space.

When disinformation adopts African languages

"On WhatsApp, Facebook, or TikTok, I regularly receive fake news in Bambara in family groups. The audios, easy to download and share, promote their virality."

This vitality of local languages on social media also has a downside: they have become a prime vector for disinformation. Rumors and hoaxes exploit the proximity, trust, and familiarity offered by these everyday languages.

"On WhatsApp, Facebook, and TikTok, I regularly receive fake news in Bambara in family groups. The audios, which are easy to download and share, help them go viral," says Georges Attino.

These short, often anonymous formats circulate at high speed and reach all generations. The result: when they are conveyed in a language everyone understands, fake news appears more credible and spreads even more widely. Hence the importance of responding in the same language, to effectively deconstruct rumors and prevent false information from spreading.

These short, often anonymous formats circulate at high speed and reach all generations.

3 priority projects for inclusive fact-checking

To make fact-checking truly effective in Africa, Georges Attino identifies three priority areas:

1. Train fact-checkers in local languages

It is essential to have fact-checkers capable of producing directly in national languages, rather than limiting themselves to translations from French or English. This not only allows for greater proximity to the public, but also better adaptation to the cultural realities and expressions specific to each language.

2. Make verification tools accessible

Speakers of local languages must be able to understand what fact-checking is, how it is carried out, and what tools exist to verify information. This requires appropriate training, simplified resources, and platforms that integrate African languages, in order to democratize information verification.

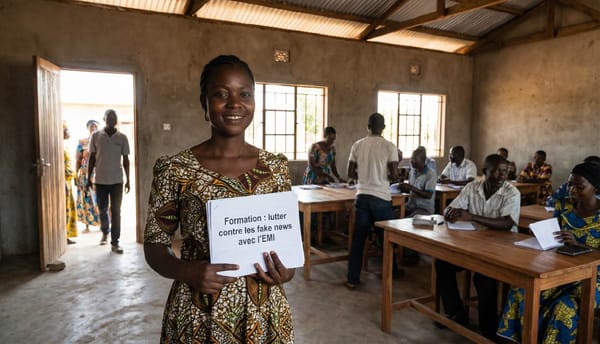

3. Develop media education in national languages

Beyond the work of journalists, every citizen must be made aware of the mechanisms of disinformation. In local languages, it is possible to simply explain how to identify a rumor, why it is dangerous to share without verifying, and how to adopt a critical approach to viral content. This basic education helps transform citizens into actors in the fight against fake news.

One thing is clear: fact-checking must not remain an elitist tool reserved for a French-speaking minority. It must be accessible to all, regardless of language.

At a time when orality and local languages play a central role in communication in Africa, their integration into fact-checking appears to be an essential weapon for curbing disinformation.

Article rédigé par Abdoussalam DICKO